Sticker

February 1, 2022

“That’s not where your sticker belongs.” My classmate’s remark cuts through my skin,

their dagger gently teasing the surface. “Yes, it is,” I shot back, “My mom told me I’m from

China, so I put it there.” The assignment was simple – place a sticker where your family is from.

“You’re wrong,” the boy taunted. I didn’t think much of his ignorant statement until he pulled

out his sharpest, finest dagger yet; “Your parents aren’t from China. Your sticker shouldn’t be in

China, put it in America or something,” the student barked. I’m not sure about you, but I don’t

remember much before the fifth grade. Regardless, that kindergarten conversation lives inside

me every day.

Cultural identity is something I’ve always had difficulty confronting. I’ve moved

mountains trying to discover who I am, only to uncover taller mountains with deep canyons in

between. I come from a small “your typical American” family; We eat turkey during the holiday

season, and I light firecrackers on the Fourth of July. I was adopted from Cangwu county in the

Guangxi autonomous region of China when I was a year old. For as long as I remember, I’ve

always known I was adopted – there wasn’t a huge reveal or announcement because there didn’t

need to be one. It’s kind of hard to not know you’re adopted when your parents don’t even have

the same hair color as you. You could say I was having an identity crisis right from the start.

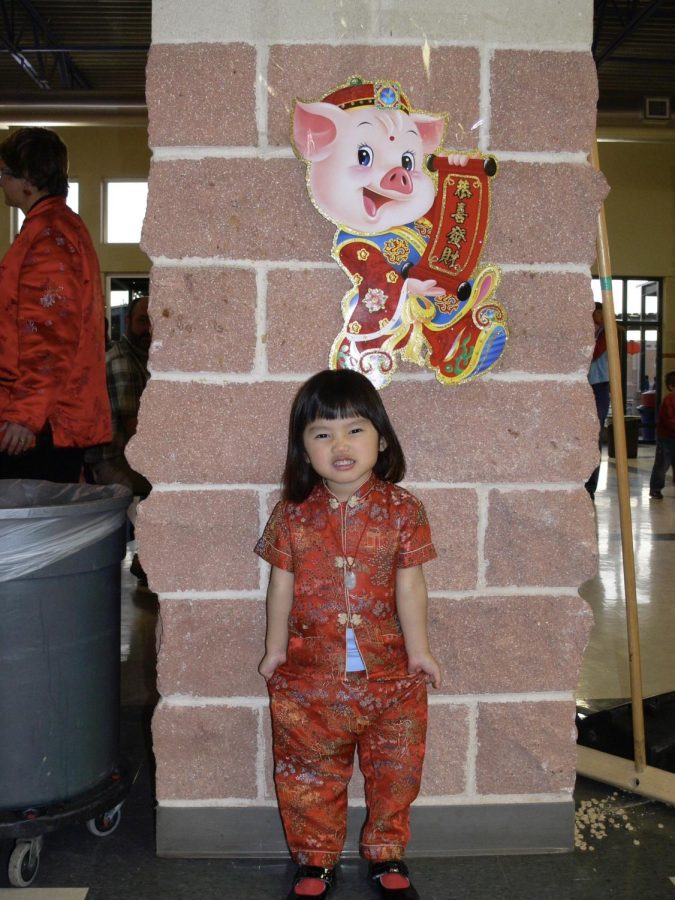

I’ll give all the credit to my mother for doing absolutely everything in her power to

immerse me in the culture of my home country. I am fortunate to have lived in Austin during my

time in the west, as Austin has a vibrant Chinese American community. I was thrown into

Chinese school, I learned traditional Chinese dance, I ate Chinese dishes frequently, and my

mother insisted that only cartoons in Mandarin be played in our Honda Odyssey as she

chauffeured me around. Soon enough I was surrounded by more Chinese language and culture

than my family’s American culture. Though I had to work much harder to keep up with my

Chinese school classmates who spoke Mandarin at home, I eventually became fluent and was

able to speak to my teachers and friends’ parents in Mandarin. After each day I would return

home to my English speaking, American family. I was torn between two opposite worlds – never

feeling completely comfortable identifying with either group.

I felt at home at Chinese school and cultural events. It was more comfortable speaking

and thinking in Mandarin – I even stopped dreaming in English. This comfort was always stipped

away whenever I went to a Chinese cultural camp for adoptees. The intent of these camps was

for Chinese adoptees to learn more about their home country and dip their feet into Chinese

language. I went to a camp like this for seven years straight, each year I become more and more

frustrated. Each year I sat through countless lessons of beginner Mandarin, bottling up what I felt

about the counselors mispronouncing simple terms. I dragged my feet to cultural lessons about

China that weren’t even taught by teachers of Chinese descent. A single thought ran through my

head every day of camp: “How do Chinese adoptees not know things about their home country?”

It’s taken years of recovery and reflection to deconstruct my emotions of the past. It’s

been humbling to recognize the privilege I had experienced learning about Chinese culture the

way I did. I am fortunate to have parents who prioritized my Chinese education. At my core, I

am a huge, jumbled, entangled mess of culture. I am Chinese American, but I’ve never figured

out how much of each one I am. At culture camp I would wonder, “Am I too Chinese to be

here?” Other Chinese adoptees don’t speak Mandarin. Other Chinese adoptees don’t attend

Chinese school six days a week. Other Chinese adoptees don’t watch Mandarin cartoons for fun.

At the same time, I strongly believe I fit in with my American parents. Around my Chinese

friends, I don’t feel any different than them. What even am I?

I’ve come to a conclusion after fighting many battles. It’s not definitive, but it provides

an outlet of peace to distract me from the mess of my tangled identity web. Ultimately, it’s hard

to confront my past because I don’t know how to begin. My cultural identity is simple, yet a

network of complex algorithms. I’m a Chinese American transracial adoptee, who happens to

speak Mandarin and can not find any ways to relate to other Chinese adoptees.

I wish this piece had some extravagant ending full of self-discovery. While my

conclusion may not reveal a life-changing finding, it gives me the hope and flexibility I need to

continue unpacking my identity as a Chinese adoptee. I’ve learned the importance of change and

forgiveness. I’ve forgiven myself for feeling embarrassed for feeling too much of something –

“too Chinese” at a family gathering or “too American” at a Lunar New Year celebration. I also

forgave the boy who rudely commented on my map sticker placement – I now like to think he

was the catalyst of my cultural identity journey. It’s completely acceptable if my map sticker

moves around. One day I could place it in China, another day I might place it in America, and

that’s okay. The flexibility I’ve given myself to explore cultures and my identity has challenged

me beyond what I had expected. My cultural identity is fluid. It constantly changes as I adapt to

life and what I’m exposed to. What is my culture? That’s up to me to decide. I may never have

the right words or be able to correctly articulate my culture, but that doesn’t matter. Wherever

life takes me, my culture will follow me from behind, being shaped by every new step I take.

Maybe one day I’ll finally know where to place my sticker.

Qai Hunzai • Apr 9, 2022 at 9:05 pm

that was amazing anna!